- Home

- Michael Byrne

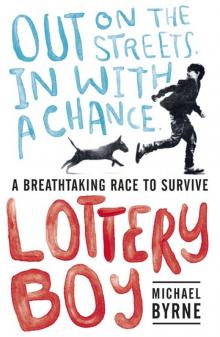

Lottery Boy

Lottery Boy Read online

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

Acknowledgements

For my daughter, Eve

“Dreams are true while they last, and do we not live in dreams?”

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Bully squinted up at one of the faces of the big, big clock across the river. Both hands were going past the six and it was time for Jack’s tea. He pulled the can and metal spoon out of his long coat pocket.

“Here you go… Here’s your tea, mate,” he said, making a big fuss of spooning it out, because there was only jelly in the bottom. Jack sucked it down without chewing.

Jack was a bull terrier, a Staffy cross, but crossed with what Bully didn’t know for sure, no one did. That other half was all mixed up bits of other dogs. Her short wiry fur was dark brown around the neck and streaked white and grey everywhere else, making her look like an old dog at the end of her days. And she had a Monkey Dog tail, and a wide back with legs that were jacked up at the rear and bowed at the front, so that when she sat up she looked like she really wanted to hug you. Her head, though, had little fangy teeth inside so that you didn’t really want to hug her.

When Bully had left the flat in the winter, Jack had come with him. It was the summer now and though she was getting on for two years old and filling out, she was still a funny-looking dog. Not a good dog for begging, but to Bully she wasn’t for begging. She was his friend and as good as family.

“Come on, mate … come on…” Bully pleaded because Jack was still looking at him and now there was nothing much left in the can. Still, he had another scrape round. Then without thinking he slid the spoon into his own mouth. It came on him like that when he was hungry – all of a sudden, catching him out, making him do strange things – like he couldn’t control it, like he was the animal.

Bully spat it out. The jelly didn’t taste so bad but it was the feel of it he didn’t like, cold and slimy in the back of his mouth. He rinsed his cheeks out with water and then from habit, to calm himself down, he read the ingredients listed on the back of the tin because he liked things that just told you what they were and didn’t try telling you anything else.

Water 65%

Protein 20%

Fat 12%…

He got down to the last ingredient, the only one that he didn’t like seeing there: Ash 3%. And he thought of all the zombies in the factories flicking their fags and topping up the cans. And the other kinds of ash they used, maybe, if they ran out of smokes. But at least they were honest enough to put it on the back of the tin.

He went to lob the can into the river but changed his mind when he saw the picture of the dog. It was a Jack Russell. And he liked Jack Russell terriers – a bit too little maybe, a bit too yappy – but what he really loved was seeing Jack’s name printed out on the label. It made his dog sound important and official. Though Jack wasn’t technically a dog. She was really a girl dog – what they called in the dog magazines a bitch. And when he’d found her all that long time ago, last summer, and brought her back to the flat, and Phil had pointed out she was a girl, he’d named her Jacky straight away before his mum got back from the hospital. Bully, though, hadn’t called her that since he’d left the flat. He’d lost the y, so she was just Jack now.

He put the empty can in his coat pocket and wandered back along the river towards the big white Eye that always looked broken to him – the way the wheel went round without moving, like the zombies stuck up there were waving for help. Jack followed along next to him, every so often nosing his ankles but never getting under his feet. Bully had trained her pretty well before they left the flat. He’d spent weeks just teaching her to stay, giving her Haribo and Skittles whenever she did it right. They called that rewarding good behaviour in the magazines.

Bully stopped when he got to the skateboard park, sucked in by the clatter of the boards and the laughter. He didn’t think much of the place though. There weren’t any big ramps or jumps, just little concrete ones no bigger than some of the kerbs and speed bumps on his old estate. He didn’t even think it was a real skateboard park, the way it was squeezed underneath the big fat grey building above. And it reminded Bully of the block of flats where he used to live, the basement underneath where the rubbish chutes fed down to the bins.

He still didn’t know any of the boys who did tricks. He just came here to watch them laughing and talking and falling off, and then blaming their skateboards for everything. One day he’d rock up with a board that you couldn’t blame anything on, with silver and gold trucks and the best decals … and it would be just the best one. He wasn’t sure when that day would be but it would definitely be a day.

“Look at ’im,” he said, pointing one of them out to Jack. “Shit, in ’e?” Secretly, though, he hoped that if he just stood there and stared long enough, one day one of them might let him have a go. So far all they’d done was call him a germ and tell him to eff off. He didn’t know exactly what a germ was in skater speak but he knew it was something little and dirty and bad. Though to be fair, when he was here with Chris and Tiggs, Chris had called them a lot worse names and thrown that bottle so that it smashed right in the middle of where they did their crappy tricks.

That didn’t happen usually. Usually they just lobbed their empties off the footbridge to watch them float back underneath. Chris and Tiggs were his mates. They said things, making him laugh, going on about girls who were pigeon and breezy, messing about along the river. Chris sometimes tied a red bit of rag round his head and Tiggs always had his big extra ears somewhere on his head, listening to his sick tunes. They were both older than him. And they had been all over the place, all over London, even up to Brent Cross shopping centre.

He watched the skaters for a bit longer until a short little boy, shorter than him, did a really crappy trick and fell right off onto the concrete slabs, rolling over and skinning his elbow and rubbing it like that would make the skin come back. Bully started fake laughing. He knew they wouldn’t do anything because he had Jack with him but he didn’t want the Feds getting wind, so they left and carried on walking towards the Eye.

At the footbridge he stared at the beggar man on the bottom step. He wasn’t doing it right. Usually, if you were begging you sat at the top where the zombies stopped to catch their breath. The man didn’t look too good either, shivering in the sun, wouldn’t be making much with his head down, mumbling to himself like that but not saying a word. He didn’t even have a sign. You had to have a sign if you weren’t going to ask, otherwise how was anyone to know?

Bully went round the beggar man and climbed halfway up the steps to the footbridge. He stopped and looked back along the river to see if there was anything worth fishing for. The sun was still warm on the backs of his legs and a long way from touching the water, not the best time of day for fishing. There were still too many zombies about, not looking right or left, but leaving town as fast as they could. And in the morning, coming back just as quick. He squinted a little more to sharpen up his eyesight. Everything wriggled in front of him if he didn’t squint. He was supposed to wear glasses for seeing things a long way away but he’d left the flat without them, so he just squashed his eyes and squinted instead.

He made out a couple of may

bes leaning over the railings, looking at the river: a tall girl in shorts and tights with an ice cream, her boyfriend smaller than her, joking about, pretending to rob it off her. Bully left them alone though. Girls didn’t like dogs but old ladies did. And there was one! With a nice big handbag on her arm large enough to fit Jack in, staring at buildings across the river like she’d never seen a window before. He went down the steps on tiptoe quick as he could, nearly tripping over the guy still shivering away on the bottom step, and came up on her blind side just as she was starting to move on.

He matched his pace with hers.

“I’m trying to get back to me mum’s, but I’m short 59 p…”

“Oh, right,” she said, but stepping back like it wasn’t right.

“I want to go home but I’m short,” he said, a little faster in case she got away.

Bully liked to make it sound as if he needed the money for something else, that he wasn’t just begging, otherwise they started asking you all sort of questions about what you were doing and why weren’t you at school. He’d learnt that.

“So can you do us a favour?”

She looked like she was ready to turn her head away, knock him back with a “no, thank you”, but then she looked down and saw Jack there.

“Oh… Is that your dog?”

“Yeah.”

“He’s a good dog, isn’t he?” she said.

“Yeah…” He nodded but only to himself and tried not to pull a face. Of course she was. Bully had taught her to be a good dog and to do as she was told because that’s what you did. You didn’t treat a dog like a dog and shout and hit it. What you did was, you trained a dog up so that it obeyed you, and then you had a friend for life.

“Have you got 59 pence then or what? I wouldn’t ask normally.” He always said this, though he never really thought about what was normal any more. Once, an old lady, even older than this one, with a hat and a stick and off her head, had taken him to a café and bought him a fry-up and they’d sat there in the warm for an hour, her telling him things about when she was a girl and lived in the countryside and had her own horse and a springer spaniel, but that wasn’t normal. Sometimes he got a whole quid out of it, often just pennies and shrapnel. Once, he got exactly what he asked for to the penny, a young guy counting it out in front of his mates for a laugh and that had really wound him up.

“How old are you?”

“Sixteen.”

“You sure?”

“I’m small for me age, innit,” he said.

She made those tiny eyes that grown-ups did when they were having a good look at you from inside their head. He reckoned he could just about pass for sixteen with his hat on. It was a sauce-brown beanie hat with black spots. And it was his. He’d remembered to take it from the flat when he left in the winter. He didn’t need to wear it to keep warm any more but it hid his face from the cameras in the station and made him taller. He fiddled with it, pulled it up to a point so that in the summer sun he looked like one of Santa’s little helpers who was way too big for next Christmas.

He was twelve but getting closer to thirteen now so that he could count out the months in between just using one hand. When he was at little school, he’d been the tallest boy in the year, taller even than the tallest girl. And already he was 167 centimetres and a bit. He had a tape measure in one of his pockets that he’d nicked out the back of a builder’s van and in old-fashioned height that was nearly exactly five foot six. And that was bigger than some grown-up men, and as big as some Feds. His mum had been tall but, thinking about it, that was because a lot of the time he’d been small. And she’d worn heels. Platform one and platform two she used to call them. Maybe his dad was tall. Maybe his dad could reach up and touch the concrete ceiling at the skateboard park. Anyway, whatever his dad was, he was definitely going to get taller. That was his breed. He’d decided this, because as soon as he was tall enough, he was going to rob a bank or get a job or something and save up and get a proper place with a toilet and a bed and a TV.

He tuned back in. She was still sizing him up.

“Sixteen … are you really?”

“Yeah, I had cancer when I was little and that shrunk me up a lot,” he said all matter of fact, because cancer did that to you. His mum, after all the hospitals, had never worn heels again.

“Oh, love. You poor love. You go and get home… Look, get yourself a good meal with this and don’t go spending it on anything else, will you?” she said, looking at him now with bigger eyes. Bully didn’t like being talked to like that. He could spend it on what he liked if she gave it to him, but his face lit up when he heard the crackle of a note coming out of her purse.

When he saw the colour he couldn’t believe it. A bluey! Jack could have tins for a couple of weeks off this, the kind she liked with her name on and only 3% ash. And he fancied an ice cream and chips for himself and a proper cold can of Coke from a shop. He hadn’t had a proper can in weeks. Bare expensive in London, a can of Coke was. A total rip-off. That was the first thing that had really shocked him when he got here on the train: the price of a can of Coke.

“There,” she said. “You get home soon.” She smiled to herself as if she was the one getting the money and walked off towards one of the eating places on the river.

“Cheers, yeah. God bless ya,” he said after her. He thought that sounded good. It was what the Daveys said: the old shufflers on the streets with spiders up their noses and kicked-about carpet faces. He’d called them that after one of them had told him his name was Dave. He’d asked for a lend of Bully’s mobile and Bully had run away and steered clear of all of them after that.

Jack growled, her quiet warning one, under the radar, just for Bully. He looked up, the queen still smiling at him from off the twenty-pound note. But he lost his smile when he saw who it was, and the dog he had with him. Bully told himself he mustn’t run – worse for him later if he did because there was Janks with his eyes shaded out and his lizard grin that said: I know you.

Janks robbed beggars all over London town. Taxing he called it. He didn’t even need the money, just got a kick out of it, that’s what they said. They said he’d come down from up north and made his money dogfighting and breeding all sorts of illegals, and the rest they said. You never usually caught him out and about in the daytime with one of his illegals. Too many Feds. But once in a while, doing his rounds, he liked to chance it, showing off one of his pure-bred pit bulls.

Nasty animals. There were a few breeds Bully wasn’t keen on but the only dogs he despised were pit bulls. He didn’t like anything about them: the way they strutted about, looking for trouble with their long, shiny, burnt-smooth faces and tiny, beady black eyes. And they had this thing, so they said – everybody said – this click in their jaws like a key in a lock that meant once they bit down and got a hold of you, they never let go. Once on the estate he’d seen an American pit bull turn on the boy walking it and even when his mates had battered it, Old Mac from the newsagent’s still had to come out with a crow bar and pry it off.

Janks’s pit bull was straining on a long lead, choking itself to get at them. And Jack’s growl went up a notch and she started taking little snappy chunks out of the air.

“Stay, mate, stay, stay, stay… Mate!”

Bully’s top half swayed and twitched like he was a rat with its paws stuck in a glue trap, the rest of him still trying to get away. He’d seen them do that – real rats gnaw their own legs off near the bins round the back of the eating places.

He managed to stagger forward just a few steps and kick Jack round behind him because Jack wasn’t good at backing down. It was one bit of her training she struggled with. She was fine round people – most people anyway – just some dogs rubbed her up the wrong way.

“You’s done well…” Janks said, getting in close so that Bully felt the words on his face. He spoke in a funny way, the words seesawing up and down, the way they did up north. His dog snapped at Jack’s face and Jack snapped back and Bully gav

e her another punt with his toe.

“I taxed you before, didn’t I?” said Janks. He pulled Bully’s hat off and let it fall. The pit bull instantly went for it – like a nasty game of fetch – and started tearing it apart.

“Grown, ’aven’t ya?” he said, ignoring what was going on at his feet.

Bully was close to Janks’s height now. When he’d first got to the river in the winter time, a long time ago, this man with the same stickleback bit of hair, the same “nice to know you” smile, had asked for a loan. And when Bully had said no, he’d taken his money anyway and given him a kicking, as if that was paying him back.

Bully had managed to keep out of Janks’s way since then.

“You want to mind that,” he said, nodding down at Jack. “My dog’ll rip that thing of yours apart. You don’t want to start facing up to me with a dog, boy.”

Bully just stood there, too frightened to work out whether to shake his head or nod.

“Calling me out, are you, big man? You giving me the eyes?” And Janks jerked Bully’s head down in the crook of his arm, pushing his face into his jacket so that Bully could smell him – a sort of sharp, sniffy smell like that stuff his mum used to spray round with – and he did his best to breathe through his mouth.

“Stay! Stay, Jack!” Bully’s muffled voice just about made it out of the headlock.

“Yeah, that’s right. Good boy,” said Janks, squeezing his neck harder still.

Bully twisted his head to breathe, looked down and saw daylight at Janks’s feet. Everyone knew he had a cut-down skewer inside his boot. He’d used it once on a guy, a big fat flubber who wasn’t showing him any respect, that’s what Chris and Tiggs had told him. And he imagined it happening the way his mum used to do their spuds in the microwave, stabbing them with a fork, quick, before putting them in: stab, stab, stab.

“What she give you?”

“Twenty…” Bully said to the feet. He heard a dog yelp.

“Well, lucky for you that’s what you owe me.”

“Mate…” he pleaded.

“Who you talkin’ to? I’m not your mate.”

Lottery Boy

Lottery Boy